It’s All Greek to Me: Thucydides in the Age of Trump

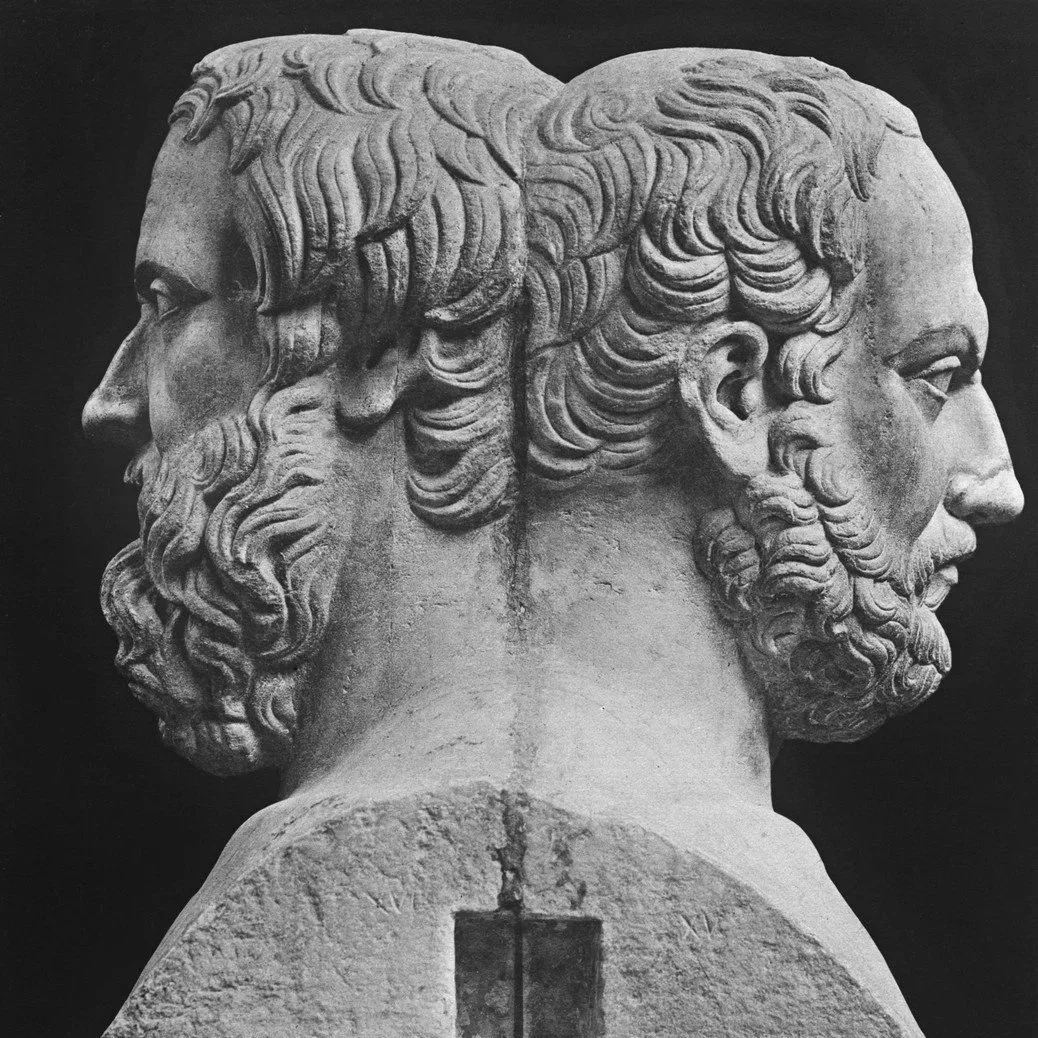

Double Herm of Herodotus and Thucydides.

Photo Credit: The German Documentation Center for Art History

The King of Melos was growing increasingly desperate.

At his gates were Athenian emissaries offering a devastating ultimatum: become a vassal to Athens or be utterly destroyed. The King implored the Athenians that as a neutral territory there was no moral need to bring Melos to heel. If the Athenians did so, the other Greek states would become hostile, seeing the Athenians as wanton aggressors.

The Athenians refused to engage in a moral debate, instead proclaiming that “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.” Desperate, the King tried all manner of other arguments, including claiming that divine favor would save him as a result of his righteous rule. The Athenians responded by insisting that it would be dishonorable to submit without a fight. At wit’s end, the King contended that the Greek kingdom of Lacedaemonia would come to their aid. The Athenians dismissed this thought with the justification that “Melos isn't important enough for them to risk an intervention.”

The Athenians made no secret of their unwillingness to become trapped in morality, reinforcing a regional order built on the assumption that “it is natural for the strong to dominate the weak, and it’s better if we are doing the domination.” Ultimately, the Melians refused to surrender and were annihilated by the Athenians in 416 BCE as part of their conquest of the Hellenic world.

For political realists, Thucydides’ Melian Dialogue is the foundational parable of world politics: power dictates morality. The only influence of ethics on policy formation is that of paranoia, justifying decisive action to the international community as a means of ensuring the state survives in a fundamentally anarchic international order.

The modern practice of realism is known as realpolitik, developed during the Cold War to counter growing Soviet influence around the world. The theory centers on the practice of interventionism, the cynical belief that covert (or overt) action taken in a foreign state, while regrettable, was optimal in achieving national security aims. For instance, the United States (U.S.) pursued regime change in Iran, Guatemala, Chile, the Dominican Republic, and Congo to prevent the spread of communism, viewing the greatest threat to national security as an ideological one.

With the Soviet Union having crumbled in 1991, it goes without saying that the age of U.S. President Donald Trump is a markedly different one. Where the Athenians and the Cold Warriors acknowledged the exercise of naked power as the spring that feeds morality, Trump insists on moral justifications while exercising overwhelming strategic dominance.

The President is currently planning interventions in both Iran and Greenland; the former to “promote democracy,” a phrase that has acquired euphemistic connotations after being associated with American interventions in the Middle East (as the “freedom deficit”), and the latter to safeguard the Arctic for the benefit of the Western world. His administration has also lambasted the states of Western Europe for their immigration policies, echoing the nativism of the former fringe right, by arguing that by “importing the ‘third world,’ you become the ‘third world.’”

It’s easy to think that Trump is the quintessential Athenian, bullying and browbeating other powers just because the U.S.’ security situation allows him to do so. I contend, however, that the President has adopted the mantle of the King of Melos, embracing empty rhetoric and strategic flailing when the U.S. occupies the Athenian position of hegemony.

Historically, American hegemony has been built on the principles of free trade and the promotion of democracy around the world. As trade dollars flowed, so did Hollywood and Springsteen, and eventually, free trade agreements and military pacts. Trump’s eagerness to increase material reciprocity over decoupling the U.S. from its painstakingly built foreign policy is perfectly Melian: hearkening back to abstract values and ethics while ignoring the reality of the increasingly multipolar world. Instead of acting in response to arms proliferation and an increasingly volatile trade environment, the President spurs foreign policy toward European states based on personal vanity and a misguided view of the U.S. as the guardian of Western values.

Donald J. Trump, President of the United States, speaks on the third day of the 56th annual World Economic Forum meeting. A uniquely inflammatory address, the President reiterated his territorial claims over Greenland at Davos.

Photo credit: World Economic Forum/Benedikt von Loebell

The President appears to understand the political consequences of basing his foreign policy on fuzzy concepts and recently offered a national security rationale for acquiring Greenland: that if the United States does not do so, Russia or China will.

At first glance this seems Athenian; the President recognizes the anarchy of the international order and seeks to maximize American hegemony. Yet, this is the most un-Athenian tendency of all. The Athenians did not conquer indiscriminately or attempt to beat already-allied states into submission. Their conquests, when understandable and necessary to ensure state stability, promoted a relatively ordered regional order. Only when the Athenians sought total domination did destabilizing war break out in the region.

In contrast, the exercise of Trumpian power is justified for the powerless and applied by the powerful. Whether the U.S.’ ego in subverting the international order will be our undoing, like it was for the Athenians and great powers throughout history, depends on the mealy-mouthed Melian leading us.