Headache at the US-China Negotiating Table: The Minerals That Had Washington in a Chokehold

Rare earth ores typically range between silver to black in their pure form. They must be refined and crushed into fine powders to be used in manufacturing.

Photo Credit: Terrance Wright

Neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium, terbium, and europium — these are five minerals frequently brought up at trade talks. With hefty price tags, they can be refined into tools that power homes, defense and the clean energy transition. These five critical substances are among the 17 nearly indistinguishable lustrous silvery-white soft heavy metals — coined the rare earth metals — that exist in the Earth's crust. Despite their name, these substances are quite abundant. However, they exist as trace impurities — minute concentrations of target chemical elements within a larger material — and are difficult to isolate. Because of their necessity in products crucial to United States (U.S.) defense technologies, as well as in everyday products, these metals are giving China an edge in its trade war with the U.S.

On “Liberation Day,” April 2, 2025, U.S. President Donald Trump issued sweeping executive orders escalating the trade war that began in his first term. Executive Order 14257 declared a national emergency over the U.S. trade deficit and invoked the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to authorize sweeping tariffs. The White House issued 34% tariffs across all Chinese goods and higher duties on particular sectors (e.g. fentanyl precursors), amounting to an overall 145%. These were negotiated down a month later.

The U.S. has continued on the offensive. In September, the U.S. Department of Commerce closed a loophole on restricted party lists, subjecting entities that are over 50% owned by companies on the Entity List and Military End-User (MEU) list to trade restrictions. Entities on this list are generally considered threats to U.S. national security. Prior to the policy change, parties could use subsidiary third–party companies to procure U.S. items. In effect, this move complicated China’s import of U.S. materials, an action deemed “egregious” by Chinese officials.

China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) headquarter, located in the Dongcheng district of Beijing.

Photo Credit: N509FZ

In response, China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) issued broad unilateral export controls on rare earth materials on October 9. As a result, provisions to control rare earth items of Chinese origin became effective immediately. This includes controls over five rare earth materials, certain superhard materials and equipment and technologies in rare earth mining, as well as rare earth production lines. MOFCOM’s extraterritorial assertions, which went into effect on December 1, required licensing for foreign company-produced items that incorporate Chinese-origin rare earths and items produced outside China with Chinese technology. Simply put, MOFCOM threatened to restrict export of nearly all rare earth elements. Export applications for foreign military purposes will also be categorically denied. Because rare earth metals are pertinent for defense technologies, this ban would massively impact American defense capabilities.

On October 14, the U.S. broadened the trade war by imposing fees on Chinese ships docking at American ports under Section 301 measures of the Trade Act of 1974. This effort authorizes the United States Trade Representative to take “all appropriate and feasible action” to obtain the elimination of “unfair” trade practices.

For Washington, China’s demands were too grave; the nation simply cannot afford heavyweight sanctions on its rare earth imports. The U.S. imports 80% of its rare earths elements, among which 70% originate from China. The rare earth elements are crucial to the manufacturing of everyday technologies and defense equipment. For example, neodymium can be refined into rare earth magnets — permanent, lightweight magnets that can be used to manufacture mobile phones, medical equipment and electric cars. Additionally, certain elements power defense technologies such as radar systems, submarines and Tomahawk missiles, among others. Though there are two rare earth mines in the continental U.S., nearly all products are still sent abroad for refining.

The Virginia-class submarine, expected to be in service until at least 2060, requires 4,600 kilograms of rare earths each to manufacture.

Photo Credit: Defense Visual Information Distribution Service

As illustrated, China has an industry monopoly on the production and refinery of rare earth materials, giving it a fundamental leverage in the trade war. It controls 90% of the world’s rare earths processing capacity. This leverage has been decades in the making. However, after the 1949 discovery of trace minerals in Mountain Pass, CA, the U.S. entered the rare earth market. President Nixon’s opening of relations to China created a friendly atmosphere that facilitated information exchange. Molycorps was an American processing company that operated at the Mountain Pass mine. In the 1980s and 1990s, Chinese executives toured their facilities, taking photos and learning about Molycorp’s technologies. Soon after, hundreds of mining and processing firms popped up across China, taking advantage of China’s cheap electricity and lax environmental regulations. But, Beijing began to set production and export quotas. By 2011, the Chinese government squeezed out private sectors and consolidated the rare earths industry into six state-owned firms, setting the supply and price of rare earths for the rest of the world.

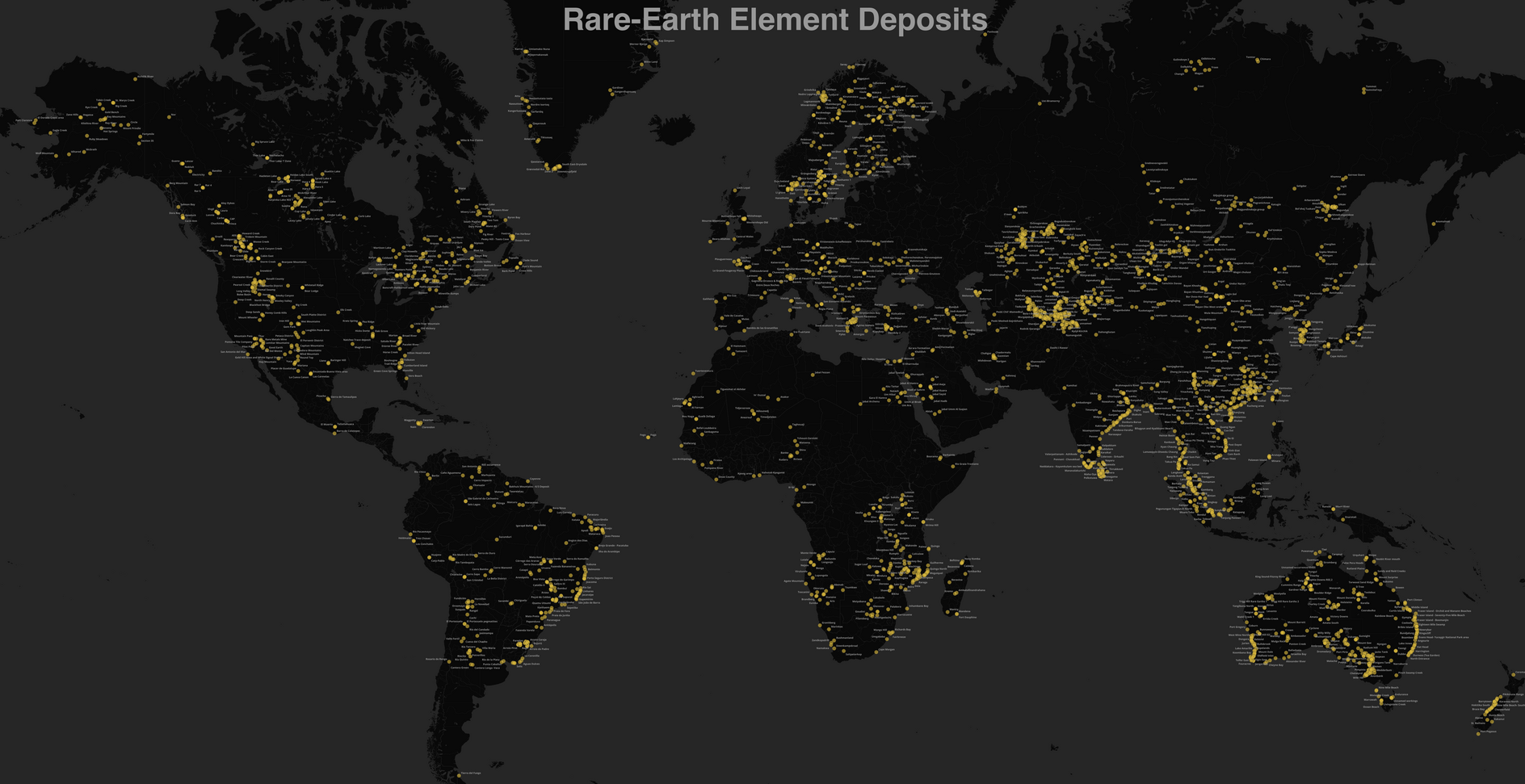

A visualized map of the known rare earth deposits and occurrences worldwide. Data from 2018.

Photo Credit: Wikideas1

As the Chinese government has been at the core of developing its nation’s rare earths industry, monopolizing rare earths serves Chinese political interests. Fully controlling the supply chain of rare earths is one way to win the trade war, cementing China as the dominant global center of economic power. The centralized structure of the Chinese government allows Chairman Xi Jinping to weaponize rare earths in the trade war with the U.S. with little blowback. China’s economy is partially state-directed and based on top-down implementation. Researchers found that as of 2019, 78% of China’s largest 1,000 private owners have equity ties with a branch of the government, or a government-owned firm. As such, the Politburo Committee, the six men who lead China, are influential over the economy in ways that the U.S. and its Federal Reserve are not.

Chinese Prime Minister Xi at the 2025 China Victory Day Parade, alongside other prominent world leaders.

Photo Credit: President of Russia

Contrarily, the White House is still governed by public opinion. Theoretically, the U.S. has economic weapons in its arsenal to respond aggressively if it deems China’s economic expansion in the global economy as a significant enough threat. However, rare earths remains a chip on the U.S.’s shoulders at the negotiating table. The pursuit of hard tactics will most definitely be met with reciprocal tariffs and rare earths restrictions from China, hiking up prices for American consumers. It is difficult for any administration to impose these sweeping and decisive sanctions because voters will feel the economic effects in their daily lives. Alternatively, Washington could ease tensions, complying with China’s demands until the U.S. can find an alternative source of rare earths. In doing so, Washington would certainly suffer a bruised ego alongside a diminished global standing.

The U.S. has the capability to achieve rare earth independence from China if it deems such an endeavor necessary for economic security. There are an abundance of rare earth deposits in the continental U.S. and Alaska. However, only one mining and processing facility exists in the continental U.S.. In 2017, the U.S. Geological Survey launched the Earth Mapping Resources Initiative to discover new deposit sites. Based on these results, exploration is underway at sites in Wyoming and Montana. But because of historic dependence on mineral imports, it will take time to install the necessary technologies and personnel before new mines can open up. Traditional mining takes between 6-18 years from exploration to production. The U.S. is also notoriously slow when it comes to processing capability developments due to logistical challenges.

Regardless, rare earths are China’s upper-hand in the trade war. Until the U.S. can decouple its rare earths dependence from China, any potential offensive move will backfire tremendously on critical U.S. supply chains.